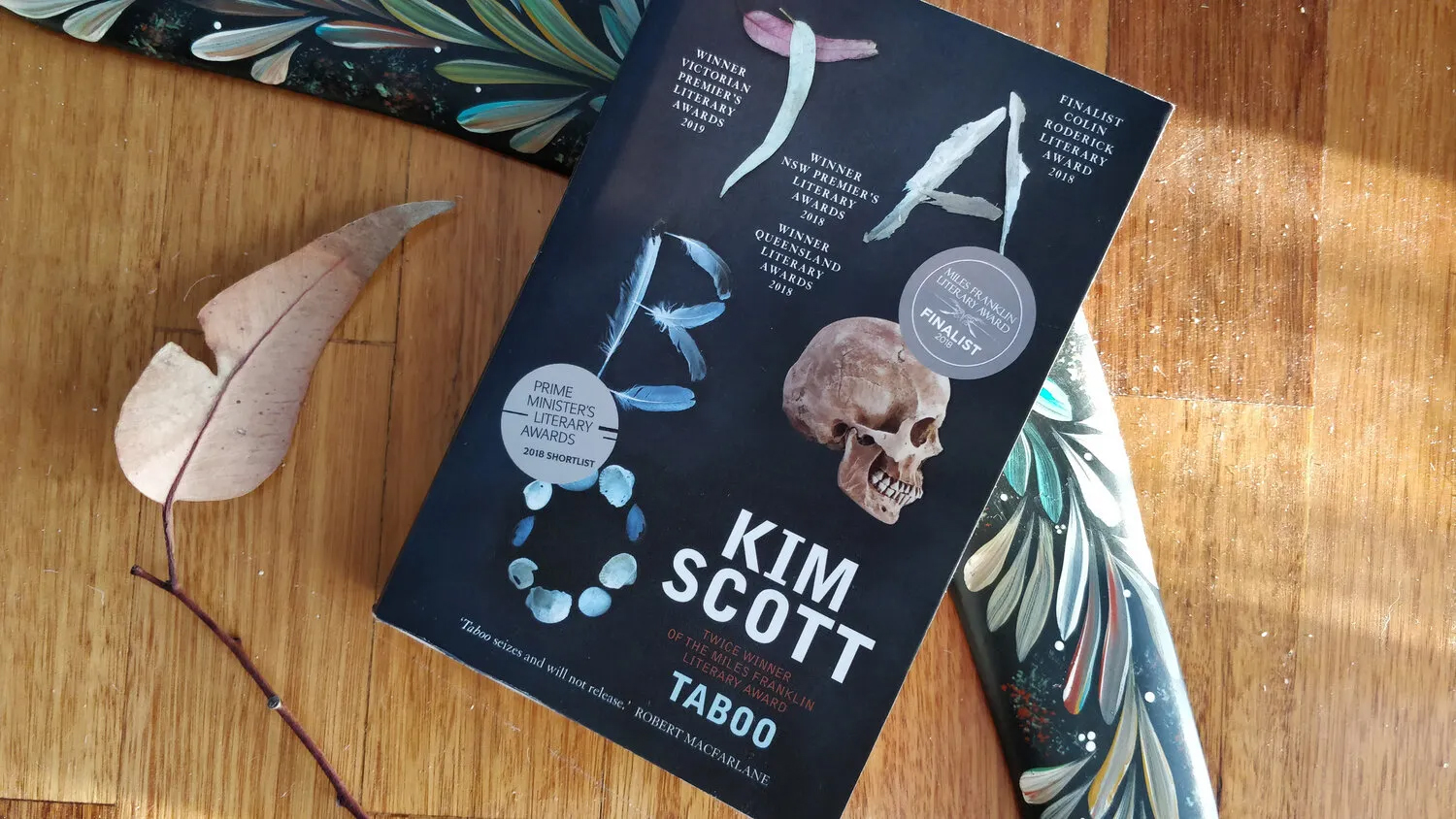

Taboo by Kim Scott

“He heard a human voice singing, and moved toward it. Yes, a song in language. Then a crack of thunder, and his whole body seemed a chamber for that great voice, and he was shaping his renewed breath, had become an instrument for this old sound.”

Taboo opens with a scene worthy of a cinematic blockbuster: an out-of-control truck careening down a dusty rural highway, narrowly avoiding pedestrians and buildings, spectators spilling from the local pub to look on in horror and awe. Before we even know what we are looking at, we’re presented with a striking image: a figure emerging from the chaos… glowing, iconic, like a deity, like a phoenix rising from the ashes.

The rest of the book is essentially a flashback, taking us back through the preceding weeks and months and years so we can understand what events have led to this opening scene. It’s not a simple thing to unravel, because when it comes to the invasion of a country, the dispossession of a people, and the conflicts that arise for all the years thereafter, these are long chains of causality.

Thin stem of smoke, rising. The fire hissed, cracked, its many small tongues licking the wood; hummed like some animal relaxed and breathing in the throat.

In Taboo, Kim Scott explores the impact of loss of country and culture on an indigenous community in south-west Western Australia. They are the Noongar of Kokanarup — a part of the country where a massacre occurred over a hundred years ago, scattering the indigenous owners of the land. The descendants of those who survived live a broken life, circling around their ancestral home, but never quite returning to the place that is now considered cursed: taboo. The current-day Noongar want to dispel the taboo and reconnect with their roots: the local council is unveiling a “Peace Park”, a symbol of local reconciliation and they’ve been invited to make a cultural contribution to the opening ceremony. Which is ironic, because for the Noongar, their loss of land has also been their loss of culture — these scattered people have lost their language, are re-learning it from the few elders who still have some words, they are re-learning the stories of their land, re-learning what art tells these stories, they’re trying to fit in, to find and gather the lost pieces of themselves.

Outside, the mallee bristled at the bus’s approach, then writhed and thrashed and shivering leaves applauded the blustering vehicle’s departure. Despite the fine soil lifting in the wind, shadows remained etched in earth: trees and fence posts, clods of ploughed soil, even a bull ant defiantly gripping the road’s bitumen edge.

None of the family is unscathed by the historic massacre. It has left a hole in the community and in each of its people. Many of the family have tried to fill this void with drugs, which has led to violence, degeneration, and prison. The novel centres around the character of Tilly, a young woman raised by a white mother. She has only recently learned of her Noongar father and then, in quick succession, met him in the prison where he was incarcerated, witnessed his battle with cancer and then mourned his death. Tilly’s lost heritage leaves a hole in her too, a lack of self-belief that leaves her vulnerable to those who would flatter and seduce her with a life of drugs and dependence.

Sand gleamed silver. The sea’s ruffled presence, whispering and sighing; was trying to tell him something. Did God speak to us this way? The sky above. A shooting star. It was surely vanity to feel so special.

Throughout, Scott tells his story with the most beautiful descriptive language, descriptions that could only come from someone who themselves comes from the land. As brutal and dark as this book is in some parts, the poetry of its prose kept me reading on. This might be a story about loss and being lost, but it’s also a story about discovery and rebirth. Amidst the despair, there is hope for the future.