The Secret Lives of Colour by Kassia St Clair

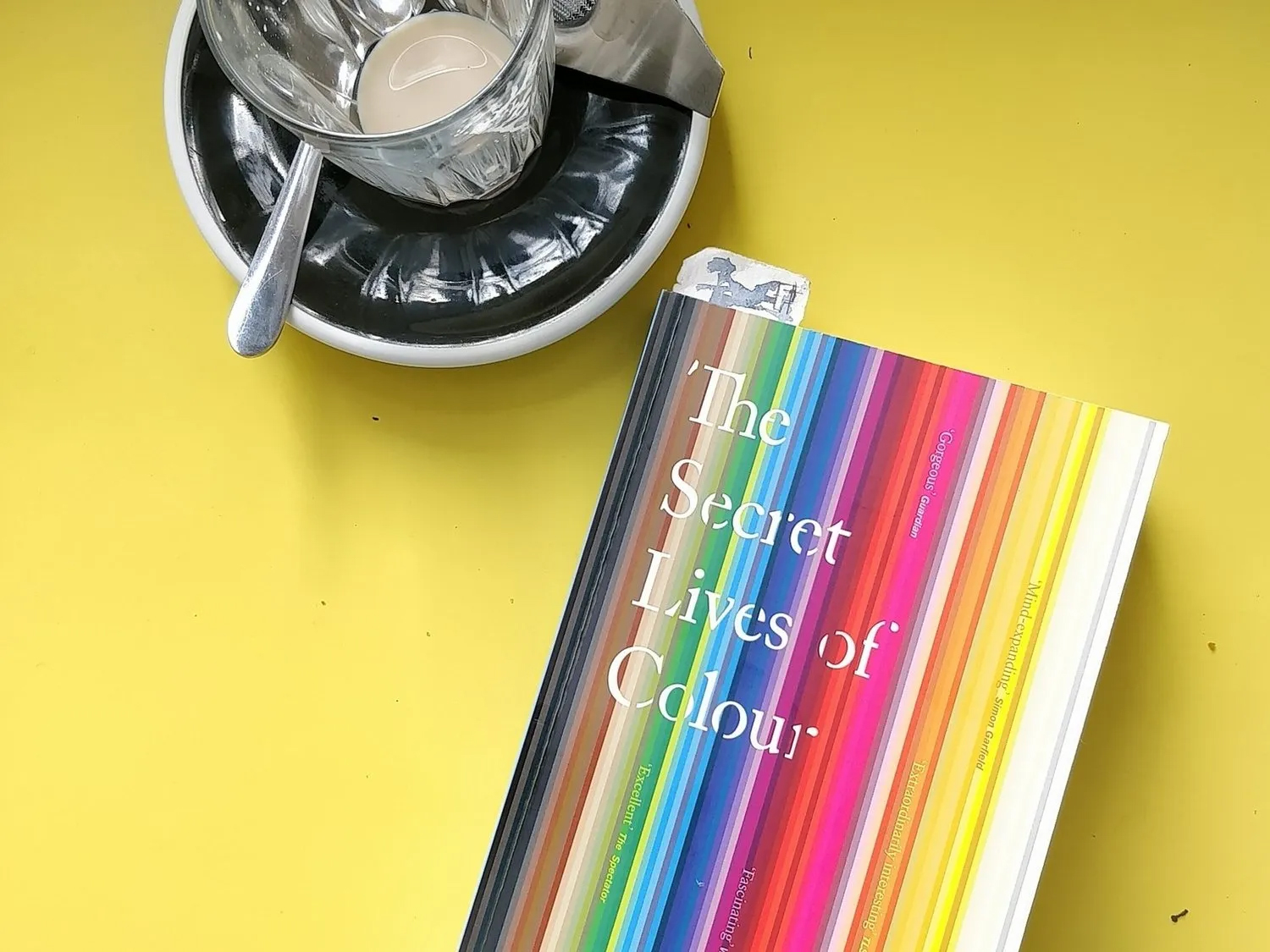

A little while ago, I posted a little write-up on how much I enjoyed David Cole’s book Chromatopia, an Illustrated History of Colour. Well, it seems that book got me thirsty for more tales of colour, because when I heard of Kassia St Clair’s book, The Secret Lives of Colour, I knew I had to get my hands on that tome also. Whilst not as pretty as Chromatopia, this paperback edition of The Secret Lives of Colour is a conveniently digestible size and progresses through the spectrum with useful and attractive colour-coded pages.

Unlike Cole’s book, St Clair doesn’t confine herself to only artist pigments — we’re also treated to such every day colours as “blonde”, “ginger”, “nude”, “shocking pink”, and “avocado”. She begins each section with an overview of the colour group in general and then moves into specific shades that have interesting stories. And such stories they are! As with Chromatopia, what left an impression on me after reading this book was understanding just how much value we humans place on colour. It moves us to great effort, leads us to construct weird social customs surrounding it, causes us to put up with disgusting substances and processes in order to produce it, and causes destruction of environment and even life. We are so desperate for the glory of rich, bright colours that we will wipe out entire species, we will soak fabrics in stinking excreta, we will live in houses coated in the same substance we use to kill pests.

In the disgusting category, I offer you the following revolting nuggets of knowledge:

- Vermillion was glazed with a mixture of egg yolk and earwax.

- Turkey Red was created via a process involving rancid castor oil, ox blood and dung.

- Indian Yellow was created by feeding cows only mango leaves and water so they would produce “extraordinarily luminous yellow urine”, which was collected and boiled down to be rolled into balls that were then dried and sold as pigment

- “Mummy, also known as Egyptian brown and Caput mortum (‘dead man’s head’) was used as paint from the twelfth until the twentieth centuries. There was some debate as to which bits of the mummy to use to get the best and richest browns…Some suggested using just the muscle and flesh, while others thought that the bones and bandages should also be ground up to get the best out of this ‘charming pigment’.”

- Tyrian purple, the colour of royalty and power, was created by cracking open certain varieties of shellfish and squeezing their hypobranchial gland to obtain “a single drop of clear liquid, smelling of garlic”. In order to get the resulting colour to adhere to and permeate cloth, the shellfish liquid was placed in a vat of stale urine and allowed to ferment for 10 days before adding the cloth.

Sounds appealing, doesn’t it? Oh yes, I’m so rich and powerful that I’m wearing this very brilliant purple cape that has been soaked in urine and garlic shellfish-gland juice and by the way do you like my shirt dyed with mummified arm? In fact, there was such demand for mummy (not only as an artists’ pigment — apparently it was considered to be quite a powerful medication also!) that the bodies of slaves and criminals were used to whip up extra mummies to make up the shortfall in supply.

From fantastically foul, let’s move on to downright dangerous, shall we? Arsenic seems to be the repeat culprit here. Orpiment, for example, is a naturally occurring, canary-yellow mineral that comprises of around 60% arsenic. Of course, this means that it is terribly poisonous and if it doesn’t kill you, it can send you literally climbing up the walls. But it’s a pretty golden colour so it’s probably worth the risk. Likewise, Victorian England was so enamoured with the colour Scheele’s green, that even after an article appeared in the British Medical Journal noting that a six-inch-square sample of green wallpaper contained enough arsenic to poison two adults, they happily continued to decorate their homes with it. It gets worse: Scheele’s green was used to print fabrics and wallpapers, colour artificial flowers, paper and dress fabrics, as an artist’ pigment, and for tinting confectionary. Mmmmmm can I have some more of those green arsenic sweets please?

And of course, there’s the old favourite: lead. We’ve all heard the stories of Elizabethan ladies poisoning themselves by painting their faces white with lead-based paint. But did you know that poisonous make-up might have contributed to the fall of the Shogun regime that ruled Japan for nearly 300 years? “Some scholars argue that breastfeeding infants were ingesting lead worn by their mothers; bone samples show that the skeletons of children under the age of three contain over 50 times more lead than those of their parents.”

Colour is so important to us, that it has even entered our lexicon. This is actually my favourite part about reading stories about colour — colour and etymology are so very closely entwined. Here are just a couple of gems from the book:

- Silver mined in South and Central America kept the Spanish empire flourishing for nearly five hundred years. It was so important to them that they named Argentina after it: “argentum” means silvery in Latin.

- “During the English Reformation, churches and parishioners used it (whitewash) to obscure colourful murals and altarpieces that depicted saints in ways they now deemed impious. This practice perhaps explains the origin of the phrase “to whitewash”, which means to conceal unpleasant truths, usually political in nature.”

- The word “beige” comes from French, where it referred to a kind of cloth made from undyed sheep’s wool. Then the word came to mean the colour of the cloth rather than the cloth itself.

- Similarly, the words “scarlet” and “russet” used to refer to types of cloth. Scarlet was luxurious and for the wealthy, and thus was usually dyed bright red. Russet was cloth for the poor and was usually dyed in shades of brown or a mixture of whatever dregs were left over from other cloth dying.

- The word “orange” as a name for colour only emerged during the sixteenth century, once the fruit was introduced to England. Before that, the colour was known as “yellow-red”.

- “Khaki” is a word from Urdu that referred to dust-coloured cloth.

Don’t worry, despite the length of this post I have not ruined The Secret Lives of Colour for you — there are many, many more interesting facts and tales to delve into. If you enjoy colour or etymology, or even just learning why some things are the way they are, then I highly recommend this book. Plus, it has a fun rainbow-striped cover: what more could you want?